Download the WhitePaper

Contraception Is Not Meeting The Needs Of People In The United States

A White Paper By The NewGen Contraception Project

FAQs

Acknowledgements:

The drafting of this white paper was a collaborative effort between NewGen Contraceptive Project (Sarah Cairns-Smith and Helen Jaffe) and two consultants (Chelsea B. Polis and Lucy Wilson). SCS, HJ and J. Joseph Speidel drafted the introduction and conclusion.

CBP drafted Sections II, III, and IV. LW drafted Sections V and (with SCS) VI. J. J. S. reviewed the entire document and made substantive comments and contributions to the final version of the white paper.

All final wording was determined by NewGen Contraceptive Project and J. Joseph Speidel.

We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of our NewGen research associates to this paper: Zoe Matticks, Alyssa Kulmer, Amy Liu, Chloe Diggs and Emily Thompson Glass.

Overview

-

Introduction: What is the White Paper Aiming To Do

-

Lays out the contraceptive options, a baseline to examine the degree to which contraceptives are meeting user needs and factors driving the gap between high use and high levels of unintended pregnancy

-

Look at the contraceptive experience from three perspectives

Section III – Views the key factors that influence contraceptive decision making

Section IV - Examines what drives contraceptive use and nonuse, continuation and discontinuation and the available evidence on contraceptive satisfaction levels

Section V - Takes the data presented in Sections II-IV from the perspective of underserved populations

Taken together sections II-V attempt to outline the current state of contraceptive usage and dis/satisfaction with existing options -

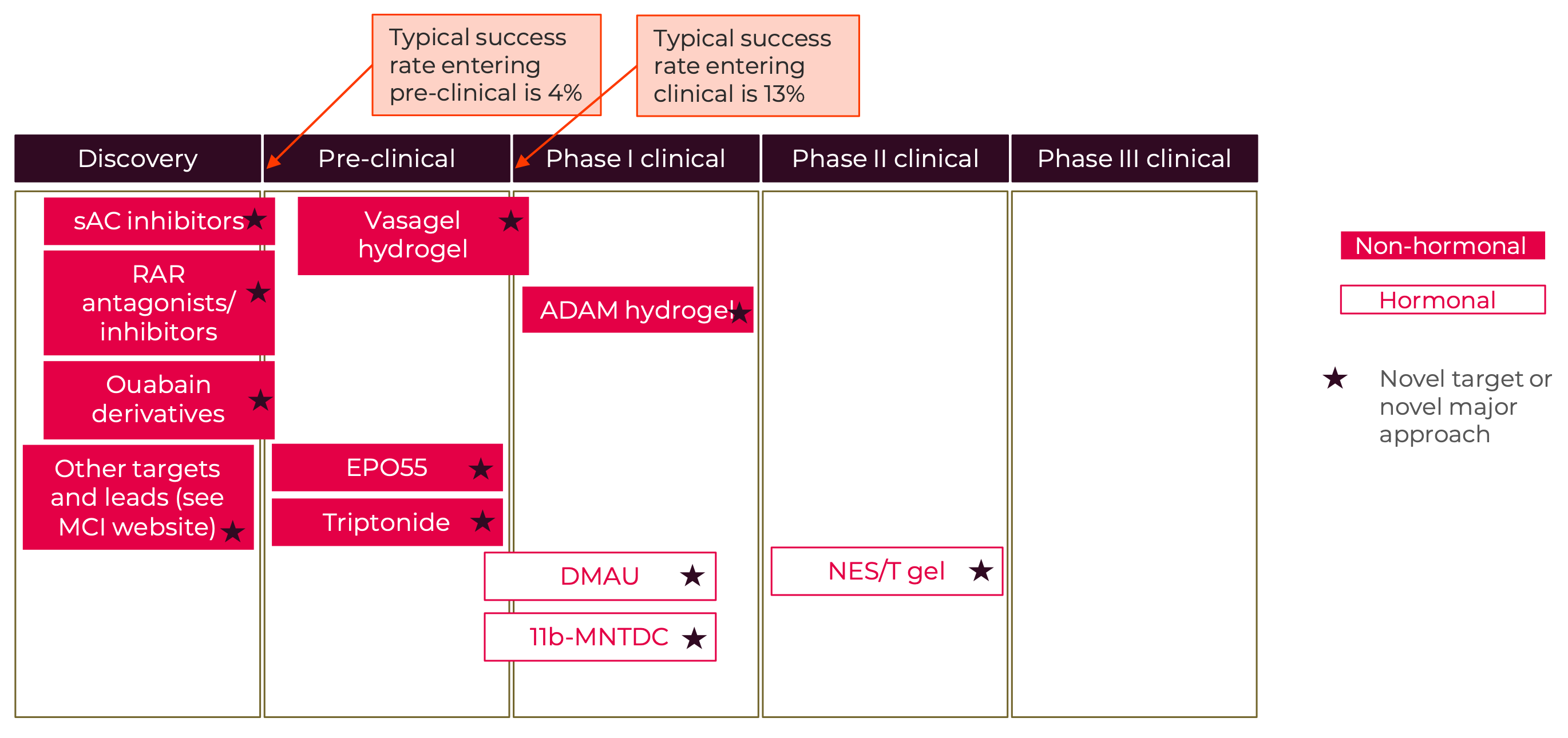

Switches focus from user needs to the state of the field of contraceptive R&D

-

Summarizes the major gaps in the current contraceptive options and makes a call for increased investment to create a new

generation of contraceptives -

Appendices A - F

-

Terms and Abbreviations

-

The references used in the main white paper

Abstract

This white paper describes why contraceptives are not currently meeting people’s needs in the United States. Women+ are experiencing high rates of contraceptive failure, unintended pregnancies, and many experience a high level of dissatisfaction with available methods. Men+ have few options. Yet the level of interest and investment in contraceptive research and development (R&D) is very low. This paper makes the case for more investment in contraceptive R&D - to improve our understanding of reproductive biology, to discover more contraceptive targets, to apply advanced science in the discovery of new product options, and to fund the testing of those options in clinical trials. Renewed interest and investment in contraception is essential for us to have a New Generation of Contraceptives and improve on our current experiences with contraception.

Section I: Introduction

This report documents why the array of contraceptive methods currently available to people in the United States is not meeting their needs. Evidence for this assertion includes the following: 1) Women+ are experiencing high rates of contraceptive failure and unintended pregnancies; 2) Survey research has established the desired characteristics of contraceptives and reveals a substantial level of dissatisfaction with available contraceptive methods; 3) The current array of contraceptive methods has clear gaps and therefore is not meeting the specific needs of many different groups of existing and potential users; and 4) The level of interest and investment in contraceptive research and development (R&D) is very low, in part because the extensive use and apparent diversity of existing options drive a mistaken perception that contraception is a “solved problem.”

For more on this topic, see also our commentary in Contraception, June 2024 (Cairns-Smith et al., 2024).

Section II

This section lays out the major contraceptive options and their relative popularity and effectiveness. This creates context from which to examine the degree to which contraceptives are meeting user needs and the factors driving the gap between high contraceptive use and high levels of unintended pregnancy.

Section II: Contraceptive options: The current state of contraceptive usage in the United States

Contraceptive failure and unintended pregnancies

Almost two thirds of women+ in the United States use contraception – often for decades (Daniels & Abma, 2020). Even so, nearly half (45%) of all pregnancies (about 2.5 million annually) are unintended and 42% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion (Guttmacher Institute, 2020b). Although many unintended pregnancies result from reasons such as lack of access to contraception, non-use, and improper use, many commonly used contraceptives fail, even when used correctly.

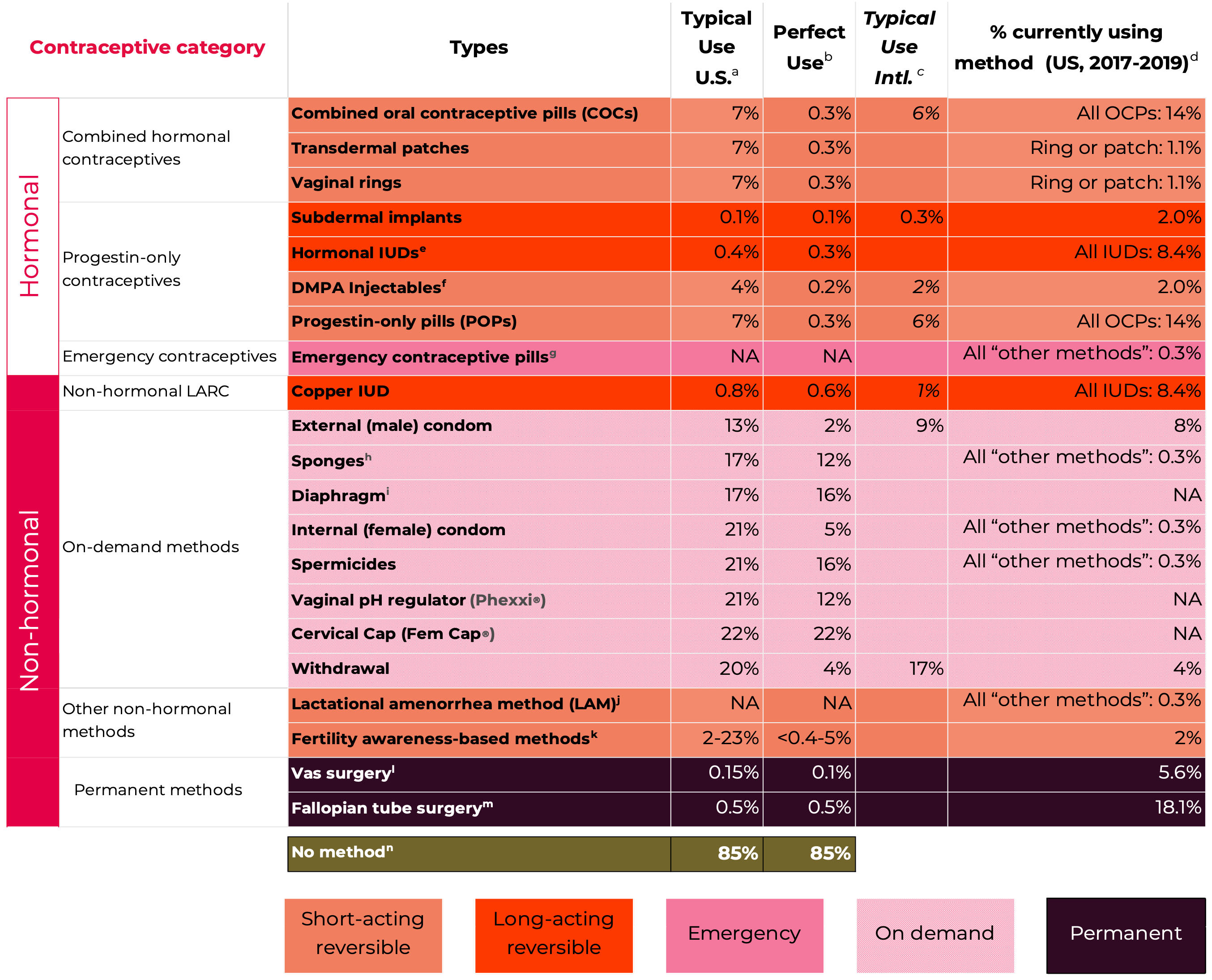

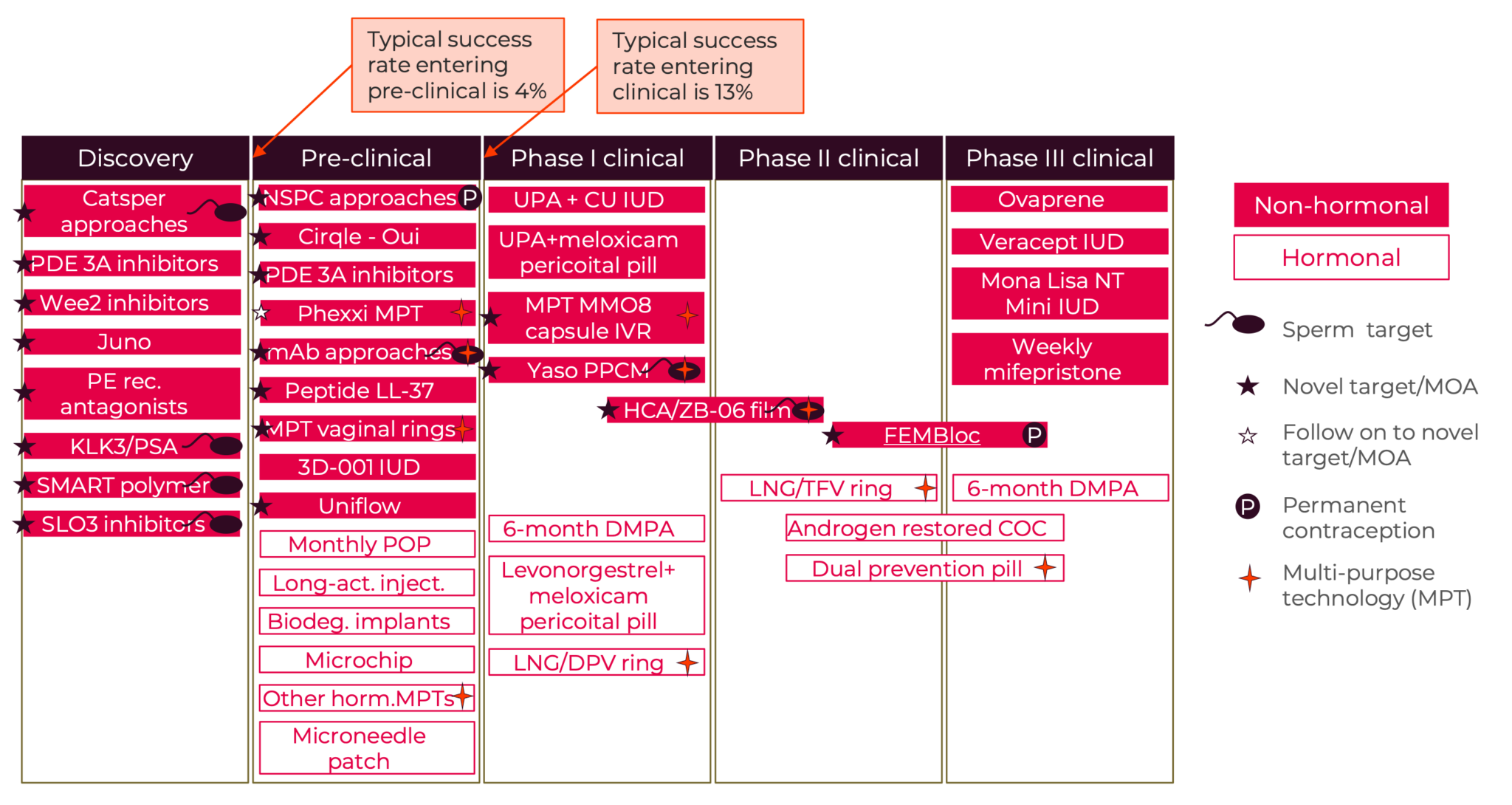

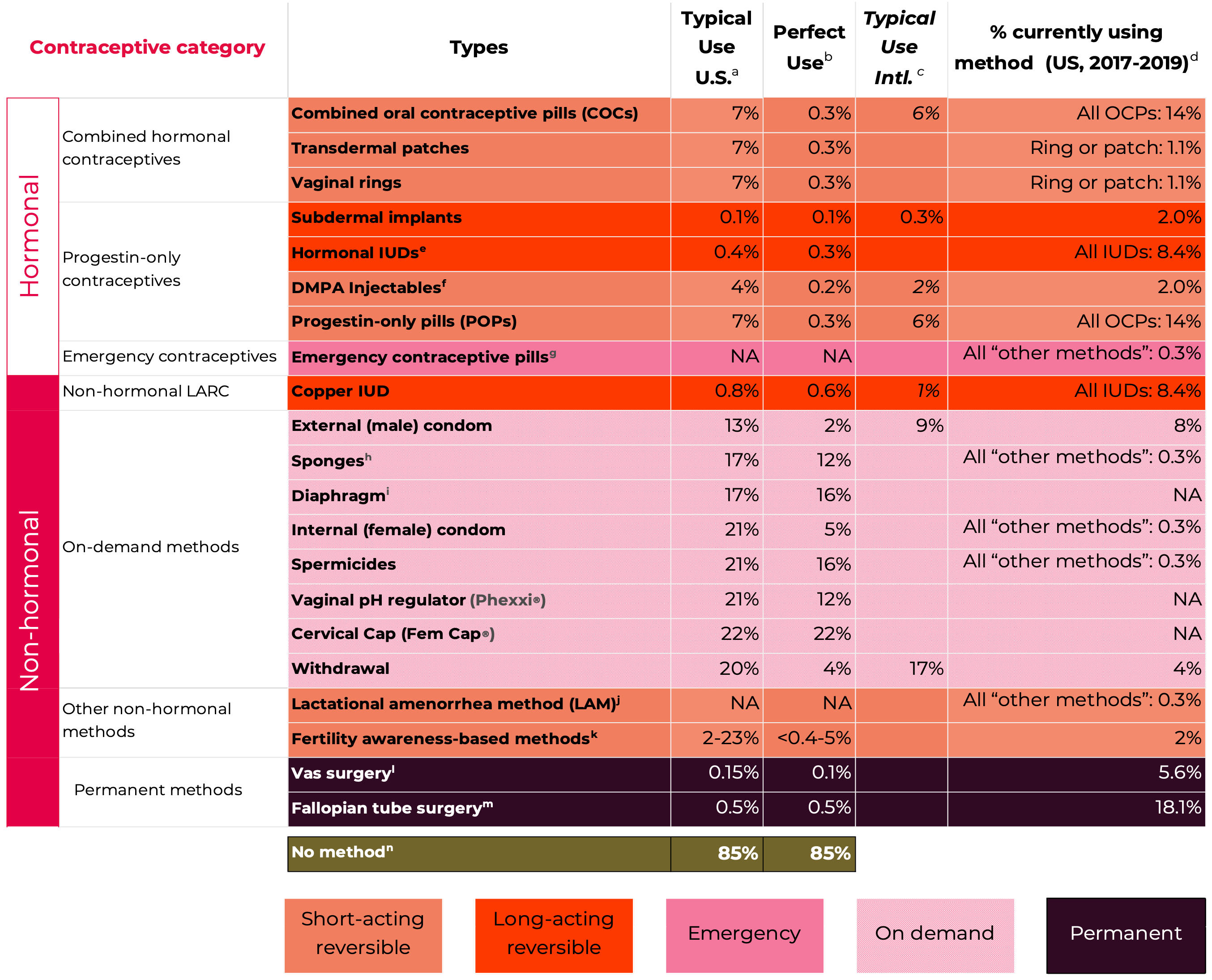

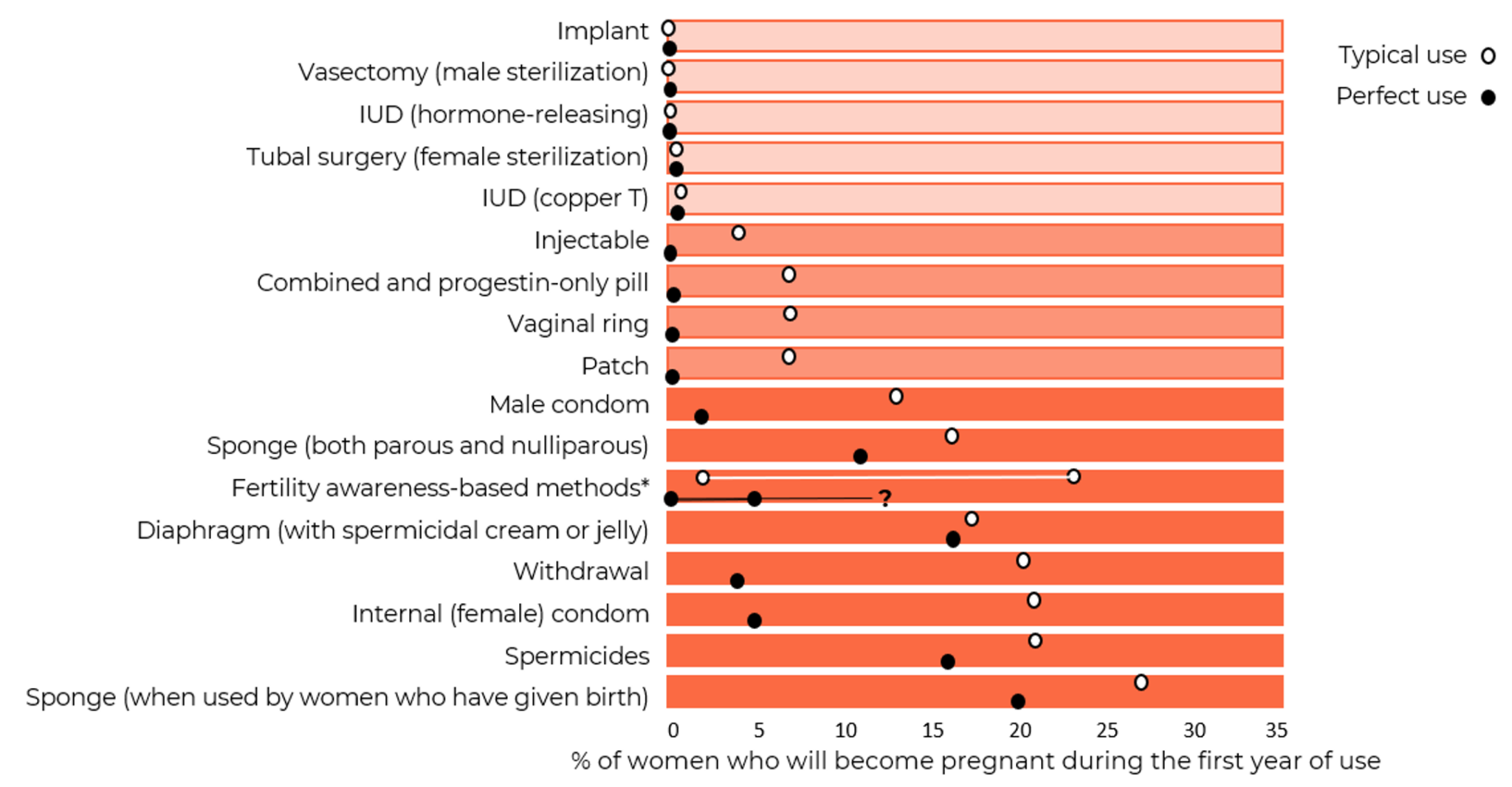

Data on the risk of pregnancy for each contraceptive method is shown in Figure 1. The most commonly used reversible contraceptive method, the combined oral contraceptive (COC) has a pregnancy rate of 7% under typical use conditions but only 0.3% a year when used perfectly in the first year of use (Hatcher et al., 2018). Similarly, the male condom has a failure rate of about 13% under typical use compared to 2% when used perfectly in the first year of use. The long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods (IUDs and implants), and the permanent methods (male and female sterilization) are much more reliable. They do not depend on conscientious behavior by their users and have pregnancy rates of 0.1% to 0.8%.

The unfortunate reality is that over many decades of typical use of currently available contraceptives there will be one or several unintended pregnancies. Even with perfect use of high efficacy methods there will be pregnancies. For example, according to a study by Tietze and Bongaarts, if all couples used a 90% effective contraceptive after having two children they would end up with a total of 2.84 pregnancies (Tietze & Bongaarts, 1975). They concluded that, “It is unlikely that any population has ever attained a low level of fertility (average births per woman of 2.2 or less) without the use of induced abortion, legal or illegal. More widespread and more effective use of contraception reduces the need for abortion; however, abortion is not likely to disappear at the levels of contraceptive effectiveness currently attained and attainable.” Given people today face almost the same array of contraceptive options as when Tietze and Bongaarts drew this conclusion, but access to abortion is being restricted in some areas, it is even more essential that we invest in new methods.

Figure 1: Contraceptive pregnancy rates and usage1

Adapted from Contraceptive Technology 22nd Edition

Notes

1 Pregnancy rates, table and notes from Contraceptive Technology, 22nd Edition (Bradley et al., 2023; Cason et al., 2023) with some adaptions – including inclusion of some data from Contraceptive Technology, 21st Edition (Hatcher et al., 2018).

a Among couples who initiate use of a method (not necessarily for the first time) and who use it perfectly (both consistently and correctly) for the first year, the percentage who experience an accidental pregnancy if they do not stop use for any other reason. Most estimates in this column come from clinical data; (See (Bradley et al., 2023)).

b Among couples who initiate use of a method (not necessarily for the first time), the percentage who experience an accidental pregnancy during the first year of typical use if they do not stop use for any reason other than pregnancy. Estimates of the probability of pregnancy during the first year of typical use for withdrawal, the male condom, the pill, and Depo-Provera are taken from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) corrected for under-reporting of abortion. (See (Bradley et al., 2023)).

c Among couples who initiate use of a method (not necessarily for the first time), the percentage who experience an accidental pregnancy during the first year if they do not stop use for any reason other than pregnancy. Estimates in this column are based on population-based Demographic and Health Survey data from 15 countries, not adjusted for under-reporting of abortion. All estimates in this column are calculated using life table data. (See (Bradley et al., 2023)).

d Data for percent distribution of women aged 15-49 by current contraceptive status, United States, 2017-2019 derived from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db388-tables-508.pdf#2, by most effective method reported.

e For details rates for specific LNG-releasing IUDs (See (Bradley et al., 2023)).

f Depot-medroxyprogesterone Acetate (DMPA, DepoProvera) injectables.

g Combined ECPs, levonorgestrel, ulipristal acetate:

If used after unprotected sexual intercourse, emergency contraceptive pills or insertion of a copper IUD reduce the risk of pregnancy substantially. However, due to methodological challenges in assessing EC effectiveness, estimates of failure rates are not included in the table. Use of emergency contraceptive pills or placement of an IUD after unprotected intercourse substantially reduces the risk of pregnancy. (See (Cason et al., 2023)).

h Estimates are for all sponge users. For nulliparous women, the perfect-use pregnancy rate is 9% and the typical use pregnancy rate is 14%. For parous women, the typical-use pregnancy rate is 27% and the perfect use pregnancy rate is 20%.

i With spermicidal cream or jelly.

j Lactational Amenorrhea Method: LAM is a highly effective, temporary method of contraception. However, to maintain effective protection against pregnancy, another method of contraception must be used as soon as menstruation resumes, the frequency or duration of breastfeeds is reduced, bottle feeds are introduced, or the baby reaches 6 months of age. (See (Cason et al., 2023)). 12-month pregnancy rates are not available for this method, which should be used for a maximum of 6 months.

k Multiple FABM methods with varying features and guidelines for attempting to predict the fertile window. Range based on Sensiplan (2% typical, 0.4% perfect use), Natural Cycles (7% perfect use), Clue (8% typical, 3% perfect use), Standard Days (13% typical, 5% perfect use), Billings (23% typical, 3% perfect use). All with U.S. typical use data. And Calendar rhythm (15% typical U.S., 19% typical International, NA perfect use). (See Chapter 15, Fertility Awareness-Based Methods, (Cason et al., 2023)).

l Vas surgery (vasectomy, male sterilization).

m Fallopian tube surgery (female sterilization).

n This estimate represents the percentage who would become pregnant within 1 year without using contraception. (See (Bradley et al., 2023)).

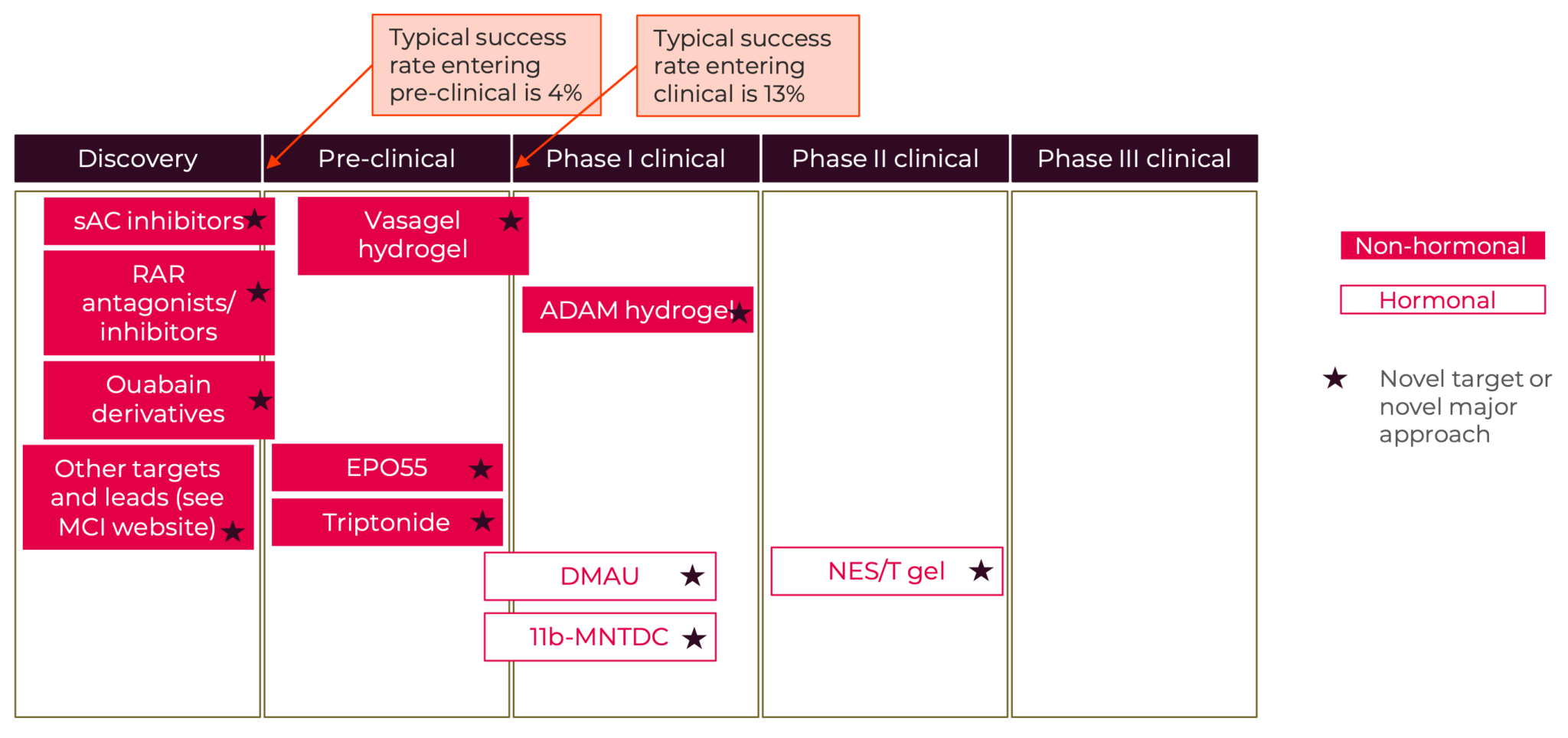

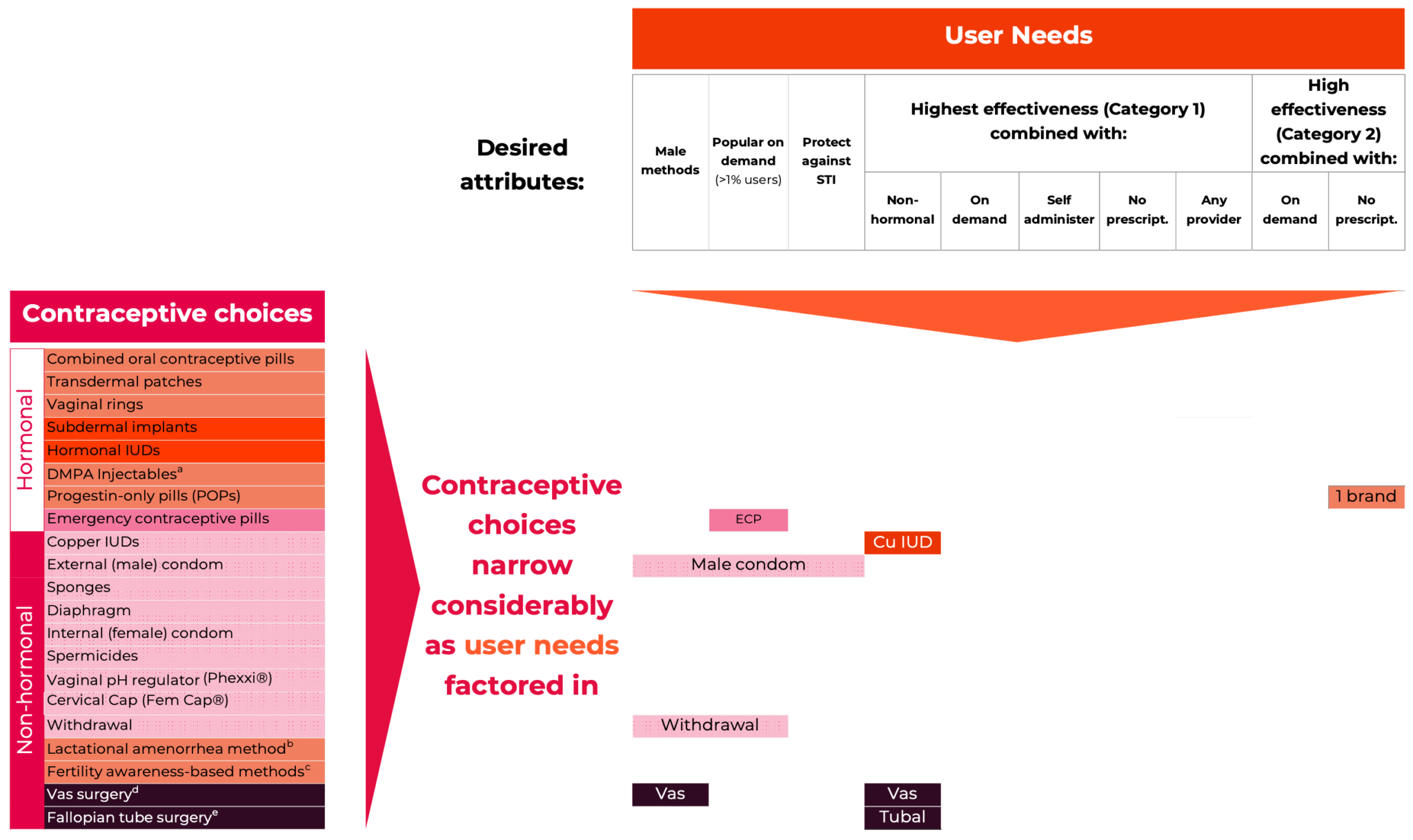

Contraceptives currently in use in the United States

Contraceptive products marketed in the United States fall into two major product classes - hormonal and non-hormonal, and four method groupings. These are:

- Short-acting reversible contraceptive methods (hormonal combined and progestin-only pills, patches, rings, injectables; and non-hormonal behavior-based methods such as Fertility awareness based-methods and lactational amenorrhea methods),

- Long-acting reversible contraceptive methods (implants and IUDs; and the non-hormonal copper IUD),

- On-demand options (spermicides and gels, diaphragms, sponges, male and female condoms, cervical caps, and emergency contraceptives may also be included in this class), and

- Permanent contraceptive methods for both men+ and women+.

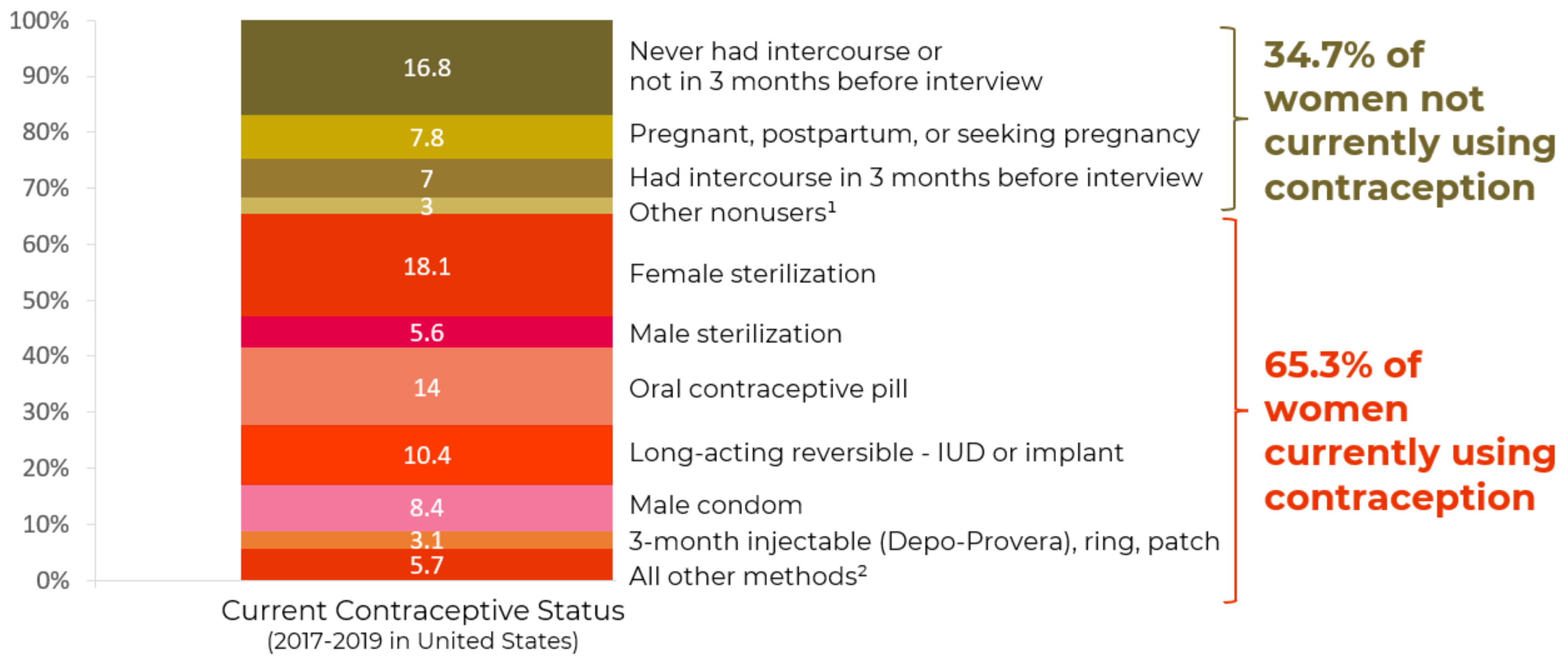

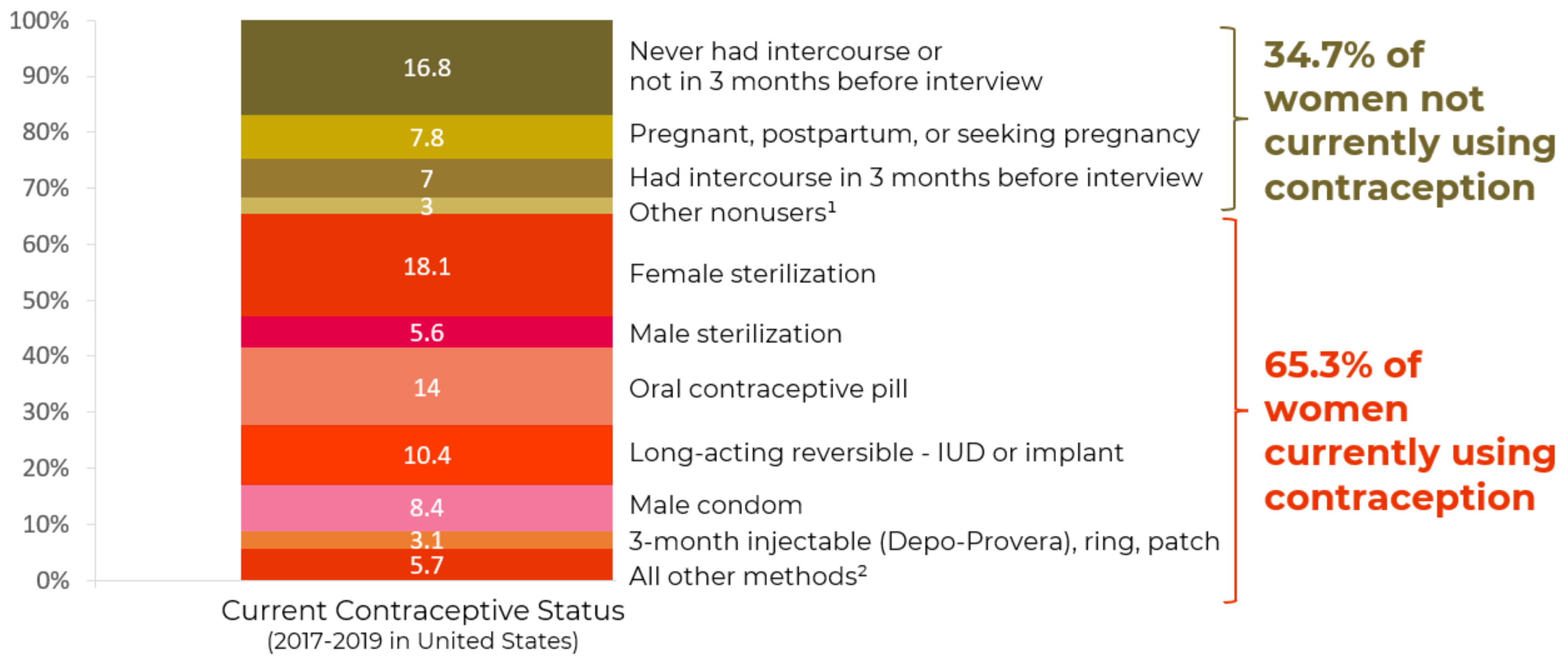

As can be seen in Figure 2, 34.1% of women age 15-49 are using the highly effective permanent (sterilization) and long-acting reversible (LARC) contraceptive methods (IUDs and implants) and 31.2% are using one of the less-effective methods.

The less-effective methods include many varieties of combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs): combined oral contraceptives (COCs) in pill form; transdermal contraceptive patches worn on the skin; and intravaginal contraceptive rings. They contain both estrogen and progestin, suppress ovulation and thicken cervical mucus, thereby reducing the chances of fertilization. Also among the less-effective methods are progestin-only contraceptives (POCs), progestin-only pills (POPs), and injectables (e.g. Depo- Provera®). POPs (often referred to as ‘mini-pills’) are taken orally every day, while injectables are delivered every three months.

The hormonal methods dominate the United States contraceptive market. The latest count was 285 individually marketed contraceptive products (Drugs.com, 2023). The vast majority are hormonals with variants on the same few ingredients in different dosage and delivery forms, with many fewer truly distinct products.

People who did not use a contraceptive method, or whose method failed can also use emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs) to prevent pregnancy. ECPs can be taken up to 5 days after unprotected sex, although taking the pills as soon as possible improves their effectiveness. IUDs can also be used as emergency contraception.

On-demand, or coitally dependent, methods have few medical contraindications. They may be appealing for people who have sexual intercourse infrequently but tend to require more user action for correct and consistent use, leading to lower typical-use effectiveness compared to hormonal or long-acting and permanent methods. Spermicides, internal (“female”) and external (“male”) condoms, and sponges are available over-the- counter, while pH-altering vaginal gels, diaphragms, and cervical caps require a prescription. Relative to the male-condom, none of these methods has so far had strong market uptake.

Other non-hormonal methods include fertility awareness-based methods (FABMs), Lactational Amenorrhea Method (LAM), and withdrawal (coitus interruptus). These methods have no side-effects, but their effectiveness is highly variable.

Figure 2: Current contraceptive status of U.S. women aged 15-49

From National Survey of Family Growth, 2017-2019

1Additional categories of nonusers, such as nonsurgical sterility, are shown in the accompanying data table: see source below

2Other methods grouped in this category are shown in the accompanying data table: see source below.

NOTES: Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding. Women currently using more than one method are classified according to the most effective method they are using. Access data table for Figure 2 at National Center for Health Statistics, National Survey of Family Growth, 2017-2019: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db388.htm.

Sections III-V

look at the Contraceptive experience from the perspective of individual users:

- Section III: focuses on decision-making

- Section IV: focuses on use/non-use, continuation/discontinuation, satisfaction/dissatisfaction

- Section V: focuses on populations that are underserved by the current method mix

Taken together sections II and III-V attempt to outline the current state of contraceptive usage and dis/satisfaction with existing options.

III: Decision-making

Section III - looks at the key factors that influence contraceptive decision-making for individual users.

Section III: Key factors influencing contraceptive decision-making

Many factors influence contraceptive method choices and satisfaction. The desired characteristics and decisions about their use are greatly influenced by an individual’s life circumstances; the characteristics of available methods; and the availability and quality of contraceptive information and services. These components vary over time, with changes potentially spurred by coitarche, relationship status transitions, changes in fertility desires, major reproductive events (e.g., birth, abortion, or miscarriage), or other life events.

A recent global systematic review of values and preferences for contraception assessed 423 articles from 93 countries around the world. The review found that values expressed by people choosing a contraceptive method centered on “themes of choice, ease of use, side effects, and effectiveness” and that “many users also considered factors such as cost, availability, interference in sex and partner relations, the effect of hormonal contraceptives on menstruation, and interactions with health workers” (Yeh et al., 2022).

Below, we briefly review these and other key factors pertinent to contraceptive selection (Coombe et al., 2016; Dam et al., 2022; Donnelly et al., 2014; Lessard et al., 2012; Madden et al., 2015; Ti et al., 2022), described in four broad categories1:

1. Real and perceived physical, mental, and sexual impacts,

2. Method- and use-related characteristics,

3. Life course and contextual factors,

4. Availability and quality of contraceptive information and services.

1. Real and perceived physical, mental, and sexual impacts

Effectiveness (and perceived effectiveness) at pregnancy prevention: A key factor that many people consider when choosing a contraceptive method(s) is how well it works to prevent pregnancy (see Figure 1) (Coombe et al., 2016; Donnelly et al., 2014; Lessard et al., 2012; Madden et al., 2015). While method-specific failure rates can be provided during contraceptive counseling, misunderstandings about contraceptive effectiveness persist (Meier et al., 2021). For example, a study of 500 non-pregnant women found that a majority (≥65%) over- estimated the effectiveness of condoms and oral contraceptives, particularly highly educated women (Kakaiya et al., 2017).

Health concerns, side effects, and side benefits: Health concerns and side effects are central to contraceptive decision-making for many individuals (Lessard et al., 2012; Madden et al., 2015). Real and perceived health impacts can deeply influence a person’s contraceptive risk- benefit calculation (Le Guen et al., 2021). A nationally representative web-based survey conducted in 2015 found that nearly half (49%) of respondents who ever used a prescription contraceptive method were concerned about side effects prior to starting, with the top two concerns being weight gain and mood swings (Nelson et al., 2018). Users of certain methods often report side effects (e.g., acne, breast tenderness, moodiness, headache, weight gain, etc.) or side benefits (e.g., reduced acne and cramping, protection against sexually transmitted infections, etc.) (Hatcher et al., 2018; Teal & Edelman, 2021). Several studies have investigated the impact of contraceptives on various psychological outcomes, such as anxiety, depression, memory issues, and more (Bitzer et al., 2018; Hatcher et al., 2018; Schaffir et al., 2016; Worly et al., 2018). Since many contraceptive studies are not placebo-controlled, understanding if certain impacts are attributable to the contraceptive method itself (vs. being due to other contextual factors, medications, health conditions, etc.) is complicated. Perceptions around contraceptive safety may be poorly aligned with current scientific evidence (for example, the inaccurate belief that oral contraceptive pills are more hazardous to a woman’s health than pregnancy is widespread (Kakaiya et al., 2017; Nelson et al., 2019)). Certain contraceptive methods are associated with rare but serious physical health risks (e.g., stroke, heart attack, blood clots, etc.), although beneficial associations also exist (e.g., reduction in rates of endometrial and cervical cancer) (Hatcher et al., 2018; Teal & Edelman, 2021).

Medical contraindications and drug-drug interactions: Contraceptive options may be limited by a person’s existing medical conditions or current use of certain medications (Marnach et al., 2020). While most contraceptive methods are considered safe for most users, particular conditions result in contraindications to use of specific contraceptive methods.

Contraceptive-induced menstrual bleeding changes: Hormonal contraceptive methods and IUDs can cause contraceptive-induced menstrual bleeding changes (including changes in bleeding duration, volume, frequency, and/or regularity or predictability). These changes can affect contraceptive users’ lives in positive and negative ways, often quite profoundly, and have been shown to be a key factor in contraceptive decision-making (Diedrich et al., 2015; Hoppes et al., 2022; Le Guen et al., 2021; Polis et al., 2018). Furthermore, different people interpret menstrual bleeding changes quite differently.

Fertility-related concerns: Although contraceptive use (regardless of duration) does not negatively impact future ability to get pregnant (fecundity), (Girum & Wasie, 2018; Mansour et al., 2011) some individuals fear that use of some reversible contraceptive methods will cause adverse impacts on their fertility (Le Guen et al., 2021). “Perceived infertility” may be associated with reduced motivation to use contraception consistently or at all, even if one is actually at risk of unintended pregnancy (Gemmill, 2018; Polis & Zabin, 2012).

Sexual acceptability: Concerns about reductions in sexual pleasure, enjoyment, spontaneity, stamina, or libido are related to avoidance of condoms and other contraceptives (Dalessandro et al., 2022; Higgins & Smith, 2016).

2. Method- and use-related characteristics

Use-related parameters: Some important use-related parameters include the duration of the fertility-regulating effect (Coombe et al., 2016; Madden et al., 2015) (and relatedly, the extent of user action required, including the frequency and ease of re-administration required and whether the method is coitally dependent (Ersek et al., 2011)), ease of use, ability to use the method discreetly, the extent of planning required to use the method, the experience of initiating the method (e.g., whether it involves pain during insertion or removal, or requires touching one’s genitals, etc. (Coombe et al., 2016)), the ability to use the method in conjunction with other products (e.g., tampons or other menstrual products) (Schnyer et al., 2019), and whether reliance on another person is required to either start and/or stop using the method.

Physical or functional characteristics of the method: For contraceptive methods which involve a physical product, that product’s physical characteristics (e.g., appearance, color, scent, size, taste, texture, flexibility, etc.) can induce emotional and psychological responses which may affect acceptability (Tolley et al., 2022; Zhao et al.,2022). Certain methods (e.g., gels, foams, spermicides, etc.), may be perceived as ‘messy’, and therefore impact the users experience (or anticipated experience). For some people, aspects such as the perceived ‘naturalness’ of the method (Le Guen et al., 2021; Woodsong et al., 2004), mechanism of action (Tong et al., 2022), route of administration (e.g., injection, oral, insertion, etc.), or mode of action (e.g., chemical, mechanical, surgical, behavioral) can also impact acceptability.

3. Life course and contextual factors

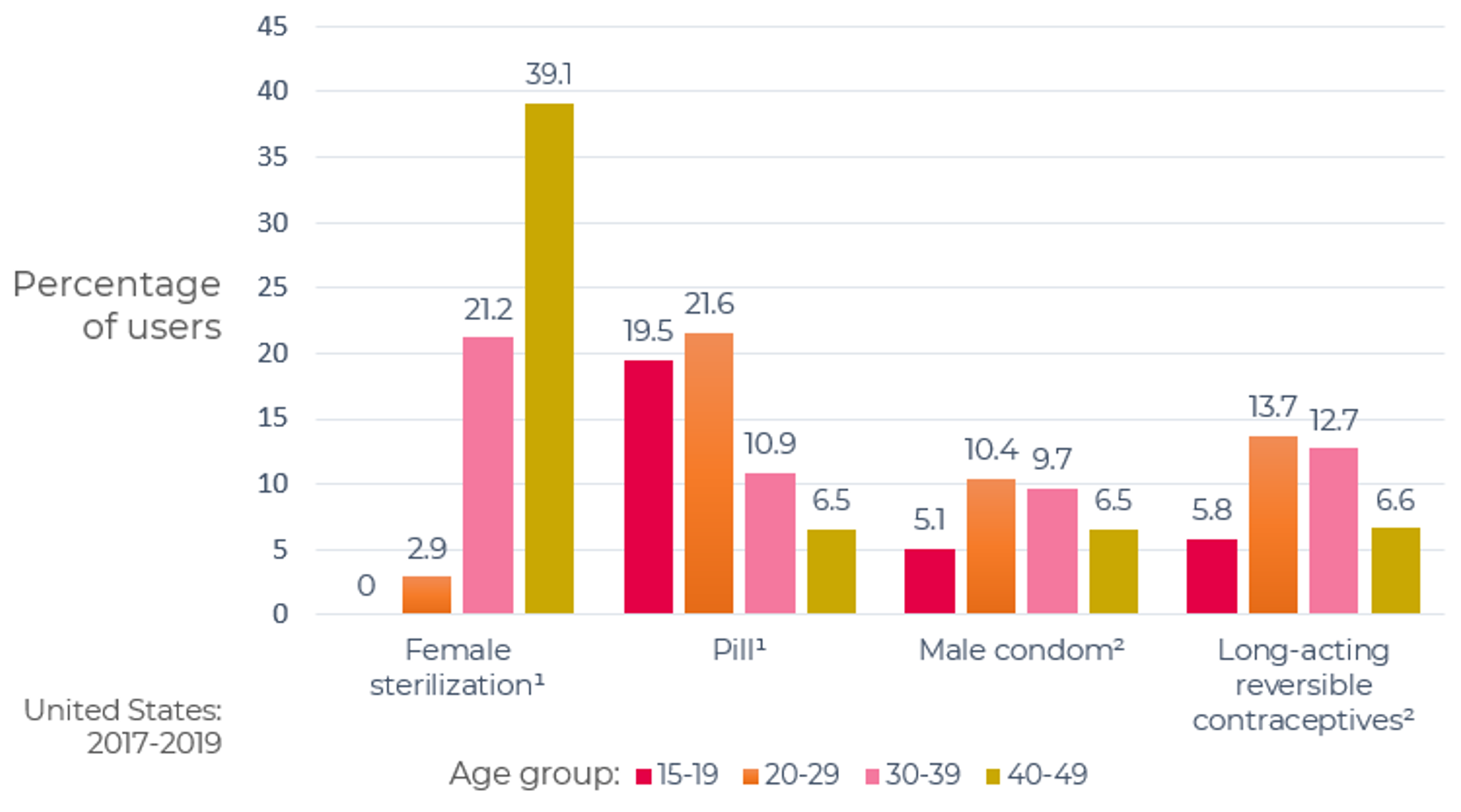

Life course factors: Where a person currently is within their reproductive journey can influence the contraceptive methods that are desirable and/or medically appropriate. Among people at risk for unintended pregnancy, age is strongly associated with stability of method use or type of method chosen (Daniels & Abma, 2020; Pazol et al., 2015, p. 20). For example, increasing age makes use of sterilization more likely and use of OCPs less likely (Daniels & Abma, 2020).

Contextual factors: An individual’s social circle may include intimate partner(s), friends, family members, healthcare providers, media sources, and more – each of which play an important role in shaping opinions about contraceptive methods (Yee & Simon, 2010), and in some cases, may also play a more direct role in shaping contraceptive choices. Several studies demonstrate that the importance of health care providers in these dynamics, while also acknowledging the importance of the role of peers and family members – but noting that they are often a source of negative or inaccurate information (Mahony et al., 2021; Yee & Simon, 2010). Beyond the influence of individual people within one’s social network, broader societal influences including religion (Srikanthan & Reid, 2008; Woodsong et al., 2004) and extent of acculturation into a given society (Gilliam et al., 2011) can also impact whether and which contraceptive methods an individual perceives as being potentially appropriate for their use.

4. Availability and quality of contraceptive information and services

Contraceptive counseling and other decision-support models: Many people rely on providers for assistance in making contraceptive decisions, and the content and quality of contraceptive counseling can impact uptake and satisfaction (Ali & Tran, 2022; Committee on New Frontiers in Contraceptive Research et al., 2004). A recently proposed definition of contraceptive counseling is “the exchange of information on contraceptive methods based on an assessment of the client’s needs, preferences, and lifestyle to support decision-making as per the client’s intentions. This includes the selection, discontinuation or switching of a contraceptive method. The key principles are based on: coercion-free and informed choice; neutral, understandable and evidence-based information; collaborative and confidential decision- making process; ensuring respectful care, dignity, and choice” (Ali & Tran, 2022). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends intentional application of a patient-centered reproductive-justice framework and use of a shared decision-making model of contraceptive counseling (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), 2022; Dehlendorf et al., 2017; Holt et al., 2020).

The 2016 U.S Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use published by the CDC recommends that common side effects (e.g., unscheduled spotting or light bleeding, or heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding especially during the first 3-6 months of use) should be discussed during contraceptive counseling and prior to, for example, insertion of the Copper-IUD (Curtis et al., 2016), as such counseling and reassurance that bleeding irregularities are not harmful may reduce method discontinuation.

Service availability and costs: Some individuals in the United States (and particularly populations that are already marginalized), face barriers to accessing contraceptive services, such as issues related to cost, stigma, or challenges in physically accessing services (Swan, 2021). For example, Power to Decide reports that more than 19 million women of reproductive age in the United States are in need of publicly-funded contraception but live in a contraceptive desert (i.e., lack reasonable access in their county to a health center that offers the full range of contraceptive methods) and 1,149,920 United States women in need live in counties without access to a single health center that provides the full range of methods (Contraceptive Deserts 2024 | Power to Decide, 2024). Furthermore, while most private health insurance plans in the United States are required to cover contraceptive methods, counseling, and services under the Affordable Care Act, 21% of privately insured women still paid some amount out-of-pocket for contraceptive care in 2020 (Frederiksen et al., 2021).

Contraceptive features desired by people in the United States

Many studies have examined which contraceptive attributes people in the United States report prioritizing in a contraceptive method.

- A 2010 survey by Lessard et al of 574 women seeking abortions in the United States suggested that the three features of contraceptive methods rated most important included: effectiveness (84%), lack of side effects (78%) and affordability (76%) (Lessard et al., 2012). This study identified substantial gaps between the contraceptive features participants desired and the features in currently available methods: for 91% of study participants, no existing method had all features rated extremely important, largely due to women wanting a highly effective method with few or no side effects. Methods involving the most features ranked extremely important were rings and sponges.

- Online cross-sectional surveys conducted in 2013 by Donnelly et al asked convenience samples of 417 women and 188 contraceptive care providers in the U.S. to rate the importance of 34 common questions when choosing (or for providers, discussing with a patient) a contraceptive method (Donnelly et al., 2014). Overall, the eight questions most frequently noted as important by women and/or providers related to: method safety, mechanism of action, mode of use, side effects, effectiveness with typical and perfect use, frequency of administration, and when it begins to prevent pregnancy.

- A 2016 systematic review by Coombe et al which assessed qualities of LARCs perceived to be desirable or undesirable by young women in developed countries identified as top qualities: no need for daily action, high efficacy, and long-term protection (Coombe et al., 2016). The review also found that while qualities perceived as undesirable for LARCs varied, the most commonly reported were irregular bleeding, painful insertion and removal, weight gain, and location in the body (Coombe et al., 2016).

Some studies examining the relative importance of contraceptive attributes also attempted to examine associations between a person’s stated attribute preferences and actual use of a contraceptive method (and the attributes of that method):

- A 2010-2011 study by Madden et al which surveyed 2590 women in Missouri reported that the contraceptive attributes most important when choosing a method were effectiveness and safety, followed by cost, whether the method is long-lasting and forgettable, health care providers’ recommendation, avoiding irregular bleeding, STI protection, and side effects (Madden et al., 2015). Every attribute participants were asked to rank was highly ranked by at least a few women – emphasizing the need for contraceptive options to meet diverse needs and preferences. Most women (69%) reported experiencing at least 1 side effect from a contraceptive method, and 65% of those women said the side effect was severe enough to cause discontinuation. Women who prioritized “long- lasting” or “forgettable” methods were more likely to choose IUDs, implants, injectables, rings, or patches compared to OCPs. Women who prioritized having regular monthly periods and avoiding irregular bleeding were more likely to choose OCPs than IUDs or implants.

- Marshall et al analyzed data from the 2009 National Survey of Reproductive and Contraceptive Knowledge, including from 715 women aged 18–29 who had ever used contraceptives (Marshall et al., 2016). Among seven contraceptive attributes, the largest proportion of respondents ranked these three as being extremely important: effectiveness at pregnancy prevention (79%), effectiveness at HIV/STI prevention (67%), and ease of use (49%). Interestingly, no statistically significant association existed between highly rating contraceptive effectiveness and actually using a highly effective method (sterilization, IUD, or implant). Conversely, rating “hormone-free” as highly important was associated with being less likely to use hormonal methods, and rating HIV/STI protection as highly important was associated with using condoms (either alone or as part of dual protection). Black and Hispanic women were far less likely (75% lower odds, and 78% lower odds, respectively) than White women to use a hormonal method, and were more than 3-4 times as likely to use less-effective contraceptive methods.

- Walker et al conducted a 2015-2016 survey of 814 sexually experienced girls and women aged 13-24 in family planning clinics in Northern California, and found that the three most highly-rated contraceptive features included: effectiveness (87%), safety (85%), and having few or no side effects (72%) (Walker et al., 2019). Age, race, and history of intimate partner violence or of an STI were associated with ratings. For example, younger women and Black, Hispanic, and Asian women were more likely than White women to prioritize STI prevention and privacy, and Black and Hispanic women were more likely to prioritize the ability to use a method without a doctor or clinic. When individuals were using a contraceptive method consistent with their preferences (on effectiveness, partner independence, and privacy), they were more likely to report contraceptive satisfaction. Interestingly, this study found no association between a strong desire for contraceptive effectiveness and current use of a highly effective method.

Prioritization of effectiveness doesn’t necessarily correlate with actual usage

While substantial variation in prioritization of contraceptive attributes exists across different studies, populations, and sub-groups, effectiveness was consistently identified as among the most important attributes. However, findings in multiple studies suggesting that stated prioritization of this attribute is not necessarily associated with actual use of a highly effective method (Samari et al., 2020). It is unclear why this apparent contradiction exists – it could be related to misunderstandings around the actual contraceptive effectiveness of various products, or to the importance of tradeoffs that contraceptive users must make when selecting an actual method – particularly when high effectiveness is often tied to characteristics that may be perceived as more invasive (i.e., requiring surgery or a device to be inserted into the body). The strong medical and public health emphasis on more highly effective methods sometimes overrides the recognition that less- effective methods which offer other attractive features may be preferred by some populations, perhaps particularly people of color, as demonstrated in several studies described above and below.

Some studies have examined why some users prefer to use less-effective methods. For example, Berglas and colleagues conducted in-depth interviews in 2016 with predominantly young Latina and African American women seeking emergency contraception, to better understand their contraceptive preferences (Berglas et al., 2021). They found that preferences centered around three main themes. The first theme was a preference for flexibility and spontaneity over continual contraceptive use. For example, some respondents preferred not to commit to using an ongoing method, and the perception of lower-efficacy methods being simpler to access and use. The second involved an emphasis on protecting their bodies from immediate side effects (e.g., weight changes, acne, depression, etc.) while also on protecting their future ability to become pregnant. The third theme involved their feelings on how well a method worked for them to prevent pregnancy. In some cases, this pertained to their clarity of understanding how the method could prevent pregnancy (for example, some felt a sense of security from clearly understanding how a condom can physically stop a sperm from meeting an egg), for others, widespread use of a given method encouraged a perception that the method must work well enough for so many people to use it.

In sum, contraceptive attributes prioritized by many United States contraceptive users across multiple studies include contraceptive effectiveness, lack of side effects (including irregular bleeding), safety, affordability, mechanism of action, ease of use, and duration of effectiveness, among others – although specifics vary by study and across population subgroups, including for minoritized women. There is a gap between the constellation of ideal contraceptive features and the array of existing methods, and data suggests that closing this gap could result in greater contraceptive satisfaction. However, it is essential to acknowledge that perhaps the most commonly-stated attribute – effectiveness – is not always reflected in the methods people actually choose to use – which may speak to the tradeoffs users must make in selecting an actual method, to misunderstandings about effectiveness, or to other factors.

Global systematic reviews suggest that counseling can play an important role in a user’s choice to use or not use a contraceptive method (Yeh et al., 2022), and so attention to the values and preferences of contraceptive providers – and whether or not these values and preferences are client-centered – is also an important component of ensuring that individuals ultimately can access methods with which they will be satisfied (Soin et al., 2022). Decision-making is also influenced by disinformation which is now potently amplified through social media, for instance there have been concerns about backlash against hormonal contraceptives based on unsubstantiated claims (Sloat, Sarah, 2022; Weber & Malhi, 2024).

1 1In aiming to provide a brief overview, we acknowledge that this list is not exhaustive, particularly for categories #3 and #4.

IV. Contraceptive use and non-use, continuation and discontinuation, satisfaction and dissatisfaction, in the United States

Section IV examines what drives contraceptive use and nonuse, continuation and discontinuation, and the available evidence on contraceptive satisfaction levels.

Section IV: Contraceptive use and non-use, continuation and discontinuation, satisfaction and dissatisfaction in the United States

Contraceptive use and non-use

Few studies in the United States have provided nationally representative information on the extent of, and characteristics associated with, contraceptive non-use among sexually active people capable of becoming pregnant but not seeking pregnancy. A study using National Survey of Family Growth data from 2011-2017 estimated that only 5.7% of women “at risk of unintended pregnancy”2 in the United States could reliably be considered contraceptive non-users (Frederiksen & Ahrens, 2020) at a given point in time. Due to variation in methodological approaches, other studies in the United States have suggested higher estimates, ranging up to 16.5% (Fowler et al., 2019; Kavanaugh & Pliskin, 2020; Mosher et al., 2015; Pazol et al., 2015). Studies in other countries suggest much higher rates of contraceptive non-use; for example, an analysis of data from 47 low- and middle-income countries suggested an average rate of contraceptive non-use of 41% (Moreira et al., 2019). In the United States, contraceptive nonuse has largely remained steady for at least the last 15 years (except among people aged 20-24, among whom nonuse increased between 2014 (10%) to 2016 (17.3%), despite increased access to more highly effective contraceptive methods (Kavanaugh & Pliskin, 2020).

Contraceptive non-use is higher in older women (Frost et al., 2007; Godfrey et al., 2016; Pazol et al., 2015; J. Wu et al., 2008), particularly those who report having difficulty achieving pregnancy or who intend to have children in the future (Pazol et al., 2015). For teens, discontinuing contraception due to dissatisfaction is also associated with contraceptive non-use (Pazol et al., 2015). Associations between contraceptive non-use and various other factors have been reported, including: being Black (Dehlendorf et al., 2014; Frost et al., 2007; Grady et al., 2015; J. Wu et al., 2008) and particularly young and Black (Dehlendorf et al., 2014), being uninsured or on Medicaid (Mosher et al., 2015; J. Wu et al., 2008), being obese (Nguyen et al., 2018), being concerned about parents finding out about contraceptive use (Iuliano et al., 2006), having infrequent intercourse (Frost et al., 2007; J. Wu et al., 2008), not currently being in a relationship (Frost et al., 2007), cohabitating (vs. being married) (Mosher et al., 2015), having perceived fertility problems (Borrero et al., 2015; Mosher et al., 2015), and holding fatalistic attitudes towards pregnancy (Frost et al., 2007; R. K. Jones, 2018). A curvilinear association has been observed between education and contraceptive non-use, with non-use more likely both at lowest and highest levels of education (Frost et al., 2007; Mosher et al., 2015; J. Wu et al., 2008).

Key reasons stated for contraceptive non-use among women at risk of (or who experienced) unintended pregnancy included: “do not expect to have sex”, “do not think you can get pregnant”, “don’t really mind if you get pregnant”, and “worried about the side effects of birth control” (Frederiksen & Ahrens, 2020; Mosher et al., 2015). A study that provided information on the relative importance of these reasons suggested that (based on nationally representative data from 2002-2010, collected among women who had an unintended pregnancy in the three years before the interview) the most frequently stated reason for contraceptive non-use was “did not think I could get pregnant” (41%) – which varied by race, with 50% of Hispanic women and only 29% of Black women stating this reason (Mosher et al., 2015). In this study, only 10% of contraceptive non-users stated that the reason was being worried about side effects (Mosher et al., 2015), though this was among the top reasons for non-use in more recent nationally representative studies (Frederiksen & Ahrens, 2020).

Non-use of one’s preferred contraceptive method is common. A nationally representative study using data from 2015-2017 found that 22% of reproductive age women at risk of unintended pregnancy in the United States would have preferred using a different contraceptive method if cost were not a factor (K. L. Burke et al., 2020).

Contraceptive continuation and discontinuation

Contraceptive discontinuation is sometimes viewed as a proxy for understanding contraceptive acceptability and satisfaction, as method- related reasons (such as concerns about a method’s side effects) play a key role in decisions to switch or discontinue contraception (Simmons et al., 2019). Ideally, contraceptive counseling can adequately prepare a user to anticipate and manage certain side effects, and inadequate counseling may contribute to contraceptive discontinuation if unanticipated side effects occur (Danna et al., 2021). Studies do suggest that method dissatisfaction is associated with method discontinuation (Frost et al., 2007) or higher intention to switch (Steinberg et al., 2021). However, some method discontinuation is due to other contextual factors (e.g., a change in fertility intentions or in sexual partners, a new medical contraindication, etc.). Furthermore, some users select shorter-acting methods because they do not anticipate long-term use (Steinberg et al., 2021) (e.g., women who wanted to become pregnant within five years were less likely to accept free IUDs or implants (Geist et al., 2020)). Shorter-acting methods may therefore appear to have greater discontinuation, even if method satisfaction was high. Still, other method characteristics may also impact discontinuation rates – for example, discontinuation of implants and IUDs generally require care from a provider, unlike discontinuation of most other methods – making continuation a passive event.

For reasons such as these, researchers have cautioned against interpreting use or continuation (sustained use) of a contraceptive method as an unambiguous indication of method satisfaction, as it may reflect merely tolerating the method (versus being satisfied with it), encountering challenges in stopping the method, or a lack of acceptable alternative method options (Dehlendorf et al., 2018; A. Glasier, 2010; Severy & Newcomer, 2005). Literature on contraceptive discontinuation has also been critiqued for failing to adequately capture and report voices of women and subjective experiences (Inoue et al., 2015).

A 2002 nationally representative study of women in the United States specified reasons for contraceptive discontinuation, which avoids some (but not all) of the measurement challenges noted above. This study found that nearly half (46%) of all users of reversible contraception reported at some point having discontinued at least one reversible method because they were unsatisfied with it (Moreau et al., 2007a). More than half (52%) of women who ever used a diaphragm or cervical cap discontinued due to dissatisfaction (Moreau et al., 2007a). The corresponding proportion for other methods included: sponge (48%), Depo-Provera® or Norplant® (42%), spermicidal foam, suppository, gel (39%), IUD (36%), oral contraceptive pills (OCPs, 29%), female condoms (24%), patch (20%), fertility awareness-based methods (15%), withdrawal (13%), male condoms (12%) (Moreau et al., 2007a). Specific reasons for discontinuation were available only for users of OCPs, Depo-Provera®, Norplant® and condoms; a majority (>65%) of hormonal method users discontinued due to side effects (Moreau et al., 2007a) (as also observed in other studies (Littlejohn, 2012)). The second most common reason was contraceptive-induced menstrual bleeding changes (particularly for Depo- Provera®) (Moreau et al., 2007a), which other studies have also highlighted as a key determinant of contraceptive discontinuation (Inoue et al., 2015; Polis et al., 2018). Condom discontinuation generally related to dissatisfaction for a sexual partner (39%) or a decrease in sexual pleasure (38%) (Moreau et al., 2007a). Discontinuation of hormonal contraception due to dissatisfaction has also been observed to be more likely among less educated women, with no differences observed by race or ethnicity (Littlejohn, 2012).

While contraceptive acceptability does not appear to have a singular, agreed upon definition in the field, Elias and Coggins wrote in 2001 that for a method to be acceptable “a potential user must fully understand the potential benefits of using it, the elements of correct use, its potential side effects, and alternative methods and be willing and able to consistently apply such knowledge to the use of the technology in everyday life” (Elias & Coggins, 2001). They suggest that studying contraceptive acceptability is important because it ultimately plays a key role in the method’s typical use effectiveness (Elias & Coggins, 2001). Heise noted in 1997 that beyond simply focusing on product attributes, “feminists have argued that ‘acceptability’ must be viewed as a complex interplay between a woman, a technology, and a service delivery environment” (Heise, 1997).

Contraceptive satisfaction and dissatisfaction

An important factor to consider in interpreting results from studies of contraceptive satisfaction is whether the study includes only current users of the method, or includes both current and former users of the method, as the latter group may include those who discontinued the method due to low satisfaction since not including them may artificially inflate apparent satisfaction measures (Moreau et al., 2007a).

Our review found only one nationally representative study of contraceptive satisfaction among women in the United States has been published since 2000. A telephone survey of adult women at risk for unintended pregnancy in 2004 measured satisfaction of women with their current method (if they were using one) or with the method they had most recently discontinued (if they were not currently using one) (Frost et al., 2007). Even among women who had continued to use the same method during the last year, only about 71% reported being very satisfied with their method (Frost et al., 2007); another 25% were “somewhat” satisfied and 4% reported being either neutral or dissatisfied (Frost et al., 2007). Among those who had switched methods or discontinued altogether, the percent of women who reported being very satisfied with their method ranged from 44%-52%, while feeling neutral or dissatisfied ranged from 15%-24% (Polis, 2022)

Limited information on contraceptive satisfaction is available from other key studies. For example, a longitudinal study (2015-2017) in Salt Lake County, Utah collected data from new contraceptive clients aged 18-45 who received their desired method at no cost (Kramer et al., 2022). At three months, 52% of participants were “completely satisfied” with their chosen method, and another 31% were “somewhat satisfied”. While 4% reported being “neither satisfied nor dissatisfied,” 7% reported being “somewhat dissatisfied” and another 6% were classified as “completely dissatisfied”. Satisfaction may have been influenced by the opportunity for participants to choose their preferred method at no cost, as well as by characteristics of the analytic sample (e.g., nearly 70% used a LARC, sample did not include adolescents, etc.).

One compelling study among women in North Carolina found that trying a LARC, even when not initially seeking one, resulted in high satisfaction. Among of women initially seeking short-acting methods but voluntarily randomized to receive LARC, 71% reported being “happy” with their LARC at the end of two years, 73% said they would use the method in the future, and 81% reported that they would recommend a friend or relative to try the method (Hubacher et al., 2018).

A study of a diverse sample of young women aged 13-24 recruited from family planning clinics in Northern California in 2015-2016 suggested that contraceptive satisfaction was higher when their current method matched preferences on any of three contraceptive attributes: effectiveness, ability to use a method independently of a partner’s knowledge, and privacy (Walker et al., 2019).

In sum, in the United States, a relatively small proportion of people (likely about 6%) but ranging up to 17% in some studies) are at risk of unintended pregnancy but not using a contraceptive method, though this may be higher within certain sub-populations. Key reasons for such non-use are not solely limited to concerns about side effects (which relate to method satisfaction), but also pertain to perceptions around the likelihood of pregnancy or attitudes towards the idea of pregnancy (which do not likely relate to method satisfaction). Those using contraception are not always using their preferred method (sometimes due to cost-related reasons), which is a barrier to contraceptive satisfaction.

The relationship between contraceptive discontinuation and contraceptive satisfaction is complex, and continuation should not necessarily be interpreted as satisfaction and vice versa. Indeed, some contraceptive continuers may be tolerating while dissatisfied with their method. A 2002 nationally representative study found that nearly half (46%) of all users reported at some point having discontinued at least one reversible method because they were unsatisfied with it (Moreau et al., 2007a). The study suggested that discontinuation specifically due to dissatisfaction was lowest for male condoms, withdrawal, fertility awareness-based methods, and the patch, while discontinuation due to dissatisfaction was highest for cervical cap/diaphragms, sponges, and Depo-Provera®.

Research that aims to measure contraceptive acceptability, including satisfaction, has faced challenges in conceptual clarity, measurement, and interpretation (Heise, 1997), and how acceptability is measured often depends on whether the product is currently hypothetical, in clinical trials, or available on the market. Quantitative studies from 2000 or later assessing multiple methods available in the general population found that 44-71% of contraceptive users reported being “very satisfied” with their method (depending to some extent on whether use was current or discontinued). While another 25-31% report being “somewhat satisfied.”

There is clearly substantial room for improvement in contraceptive satisfaction in the United States population. In these studies, certain characteristics were associated with contraceptive satisfaction, including method attributes (e.g., ease of use, perceived effectiveness, side effects, privacy), method accessibility (e.g., cost), individual characteristics (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, partnership status, health status, recency of sex), and counseling experiences (e.g., experiencing shared decision-making, not feeling the provider had a preferred method).

Some scholars focused on low- and middle-income countries argue that “the current definition of unmet need undercounts the number of women with a true unmet need for contraception as it misses the many women who are using a method that does not meet their preferences” and call for adding satisfaction questions in Demographic and Health surveys (Rominski & Stephenson, 2019). Better nationally representative estimates of contraceptive satisfaction among current and former users – ideally also including men+ – would be helpful to guide research aiming for improved contraceptives.

2 Defined by Frederiksen and Ahrens as: “not currently pregnant or seeking pregnancy, were not (or their partner was not) infecund for non-contraceptive reasons, did not expect a birth in the next 2 years, were not using contraception at the time of the interview, and either had sex that month or last had sex within the prior year while not pregnant and did not use contraception at that time.”

V. Categories of contraceptive users that are most underserved by the current method mix

Section V looks at the data presented in Sections II-IV from the perspective of underserved populations.

Taken together sections II-V attempt to outline the current state of contraceptive usage and dis/satisfaction with existing options.

Section V: Many Categories of Contraceptive Users Are Poorly Served by Current Options

The current array of contraceptive technologies has limited suitability or other drawbacks given the specific needs of many different groups of users and potential users. Sub-populations of the underserved include: groups with health concerns; groups with behavioral needs; and certain demographic and socioeconomic groups.

Groups with health concerns

People with concerns about side effects: This was the second most commonly cited reason for non-use of contraception, reported by 21% of women at risk of unintended pregnancy who were not using a contraceptive method in the 2011-2017 NSFG (Frederiksen & Ahrens, 2020)

People with contraindications to specific methods: The CDC’s United States Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (MEC) (Curtis et al., 2016) outlines these medical conditions, risk factors, and contraindications to specific contraceptive methods. The largest number of conditions and risk factors are associated with the estrogen found in combined hormonal contraception (CHC). In a nationally representative sample of women in the United States, 16% of fecund women aged 20-51 years had contraindications to CHC (Shortridge & Miller, 2007a).

Table 1: Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive use - MEC 3 and MEC 4 conditions by type of contraceptive method

| Method | MEC 3 Conditions | MEC 4 Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| All combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) |

|

|

| Initiation of CHCs |

| |

| All progestin-only methods |

|

|

| Continuation of progestin-only methods |

| |

| DMPA |

| |

| Implants |

| |

| POPs |

| |

| Oral contraceptives (POP or COC) |

| |

| Initiation of IUDs (copper or hormonal) |

|

|

Source: CDC U.S. MEC 2016 (Curtis et al., 2016)

*Indicates that the condition is listed on the table more than once, or for more than one method type.

This table does not include all contraceptive methods. For the methods not listed here, there are either few or no conditions for which use is contraindicated.

MEC category definitions:(WHO, 2015)

MEC 1: A condition for which there is no restriction for the use of the contraceptive method

MEC 2: A condition where the advantages of using the method generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks

MEC 3: A condition where the theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh the advantages of using the method

MEC 4: A condition which represents an unacceptable health risk if the contraceptive method is used

As there are many contraindications, some of which are fairly prevalent in the United States population, it would be helpful to have an estimate of the size of the population that faces contraindications. Determining this figure, however, is challenging. Estimates have only been made for contraindications to combined hormonal contraception (CHC), and most of those analyses were done to understand the risks of self-screening for over-the-counter access to oral contraceptive pills. In the only nationally representative sample of women in the United States, 16% of fecund women aged 20-51 years had contraindications to CHC (Shortridge & Miller, 2007b). In other studies, the reported estimates for prevalence of CHC contraindicated conditions varied from 2.4% - 19%, with differences in how the study populations were defined and the criteria used to define those with a CHC contraindication (Coleman- Minahan et al., 2021; Lauring et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2014). Two of those studies asked participants to self-report if they had a contraindicated condition (Coleman-Minahan et al., 2021; Lauring et al., 2016), which was found to over- estimate the actual percentage of participants with a contraindication (Xu et al., 2014).

Women+ who are postpartum: This group is at particular risk for unintended pregnancy. An analysis of 2006-2010 NSFG data found that at least 70% of pregnancies that occurred within one year of a previous birth were unintended. (White et al., 2015). Underestimating fecundability and not anticipating sexual activity in the postpartum period are common reasons for not contracepting (White et al., 2015). Potential contraceptive users also face limited options3 (Curtis et al., 2016). Postpartum use of estrogen-containing methods is contraindicated, because there is an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis, as well as a very small risk that estrogen can affect milk supply during breastfeeding (A. Glasier et al., 2019). Perceptions around the risks of using hormonal contraception while breastfeeding may also limit contraceptive use beyond the relatively short window for which it is medically contraindicated (Cwiak et al., 2004).

A greater variety of contraceptive products is needed during the postpartum period, including more highly effective, reversible methods that are non- hormonal, and particularly non-estrogenic. Methods like the progesterone vaginal ring Progering® have been developed to extend the contraceptive effectiveness of lactational amenorrhea among breastfeeding women, though this method is currently available only in a limited number of countries (Population Council, 2015).

People who are also concerned about HIV and other STIs: Most Americans will contract a sexually transmitted infection (STI) at some point in their life (Chesson et al., 2014), and the incidence of gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis are rising in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). Dual protection options that can simultaneously prevent both unintended pregnancy and the transmission of STIs, including HIV are needed. At present, condoms are the only multipurpose prevention technology (MPT) option.

Groups with behavioral needs

People who have infrequent sex: In an analysis of the 2011-2017 NSFG, not expecting to have sex was cited by nearly 14% of respondents as the reason for contraceptive non-use among those at risk of pregnancy (Frederiksen & Ahrens, 2020). (This figure was 24% for women who had experienced an unplanned birth in the previous three years in the 2006-2010 NSFG.) Nationally representative data from 2016/18 found that approximately 8% of women aged 18-44 years had sex only once or twice per year, and a further 26% had sex only 1-3 times per month (Ueda et al., 2020). People who have infrequent sex would benefit from the development of additional methods of ‘on-demand’ contraception, i.e., methods that can be used at or around the time of intercourse. On-demand options currently available are limited to emergency contraceptive pills and less-effective methods, condoms (under typical use), withdrawal, cervical barrier methods, and spermicides (Cahill & Blumenthal, 2018), as well as the recently marketed vaginal gel, Phexxi®.

People who are reluctant to interact with the health care system: Many people in the United States are reluctant to interact with the health care system, especially for reproductive health care. It includes members of racial and ethnic minority groups, for whom historic reproductive injustice as well as current experiences of racism may reduce willingness to seek products that require medical intervention (van Ryn et al., 2011). Those who identify or present as a sexual or gender minority, and youth may also be hesitant to seek health care. Reluctant groups may also include people living with a disability and people in larger bodies. As with people with limited geographic access to a health care facility and those seeking more convenience in accessing care, this population would benefit from additional self- administered options, including methods that can be started and stopped by the user.

People who want to use contraception discreetly: The ability to use a contraceptive method discreetly, without a partner’s or parents’ knowledge, is a factor in contraceptive choice and satisfaction, especially for young people (Coombe et al., 2016; Walker et al., 2019). People who lack autonomy in their relationship or are at risk of domestic violence may also want to use contraception discreetly. A variety of products is needed that do not require interaction with the health system, lead to fewer side effects (such as a lack of contraceptive-induced menstrual bleeding changes) and are not likely to be found or felt by the user’s partner, family, or friends.

Demographic and socioeconomic groups that are underserved

Men+ and others who desire male-based contraception: Currently, the overwhelming burden of reproductive control is placed on women+, as the contraceptive options available to men+ are limited. Male options include vasectomy, condoms, and withdrawal (Hatcher et al., 2018). Fertility awareness-based methods require the cooperation of both partners. (Peragallo Urrutia & Polis, 2019). Even though use of these methods results in 29% of all contraceptive use in the United States (Guttmacher Institute, 2021), men+ are often not considered to be users of contraception. More male contraceptive options are not only important to expand the options available for men+ but would also benefit couples for whom the female options are limited by acceptability, accessibility, and safety. Market research sponsored by the Male Contraception Initiative investigated interest from men+ in using male methods, they found that 8.1 million men between the ages of 15-44 in the United States would be very likely to use a new male method and 5.6 million men would be somewhat likely to use a new male method (Interest Among United States Men for New Male Contraceptive Options: Consumer Research Study, 2019). And a survey of women in three countries (China, South Africa, and Scotland) found that more than 70% of women would be willing to rely on male hormonal contraception if it were to become available (A. F. Glasier et al., 2000). A modeling study estimated that, even under conservative assumptions about uptake, introducing a male pill or reversible vas occlusion would decrease unintended pregnancies by 3.5% to 5.2% in the United States (Dorman et al., 2018).

Black, Hispanic, and people of color: Multiple nationally representative studies have reported that Black women (and potentially other people of color) at risk of unintended pregnancy are less likely to use contraception than White women (Frost et al., 2007; Grady et al., 2015; Guttmacher Institute, 2020b; J. Jones et al., 2012; R. K. Jones, 2018; J. Wu et al., 2008). An analysis of the 2006-2010 NSFG found that, among women using contraception, Black and Hispanic women were about half as likely as White women to use a highly- or moderately effective method (Dehlendorf et al., 2014). A similar result was found in a review of a 2009 nationally representative survey - non- White women were found to be 3-5 times as likely to use less-effective methods than their White peers (Marshall et al., 2016). Another reported that the racial disparity in use of highly effective contraception may be increasing over time (Jacobs & Stanfors, 2013), although this finding should not necessarily be interpreted as a negative outcome, if people are making informed trade-offs and increasingly using their preferred method.

These findings may contribute to the fact that in the 2011 NSFG, the rate of unintended pregnancies among Black women was more than double, and for Hispanic women nearly double, that of White women (79, 58, and 33 unintended pregnancies per 1,000 females aged 15-44) (Finer & Zolna, 2016; Guttmacher Institute, 2020b). In addition, Black women had an abortion rate more than three times that of White women (23.8 and 6.6 abortions per 1,000 women aged 15-44 years) in the CDC’s abortion surveillance data for 2019 (Kortsmit, 2021). As abortion access continues to be constrained as a result of the June 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization Supreme Court Decision, the impact will be particularly impactful for Black and other people of color.

Black, Hispanic, and other people of color make up nearly 40% of the United States population (N. Jones et al., 2021), and are also more likely to fall into other underserved groups, such as those with less geographic access (Kreitzer et al., 2021) and with limited resources and concerns about cost (Artiga et al., 2021; Kavanaugh et al., 2022). The intersectionality of race and ethnicity with geographic access to health care, income and education levels, and insurance status, combined with racism and discrimination in the health care system, have adversely affected the health of Black, Hispanic, Indigenous, and other people of color (Sutton et al., 2021, Roberts, 2014, (Gurr, 2011; Hooton, 2005 ). This sometimes results in a reluctance to engage with the health care system.

In considering why Black, Hispanic, and other people of color are more likely to be underserved by the current method mix, the reasons are likely to include concerns about safety and side effects, differential access to care, differential experiences with the health care system, differential preferences for various method attributes including greater interest in STI protection and on-demand options (Dehlendorf et al., 2014; Lessard et al., 2012). In the 2002- 2010 NSFG, analysis of data from respondents with a recent unintended birth showed Black women were more likely than White women to report concerns about side effects and not expecting to have sex among their reasons for non-use (Mosher et al., 2015), however, other analyses of dissatisfaction and discontinuation did not find differences in reasons among racial and ethnic groups (Littlejohn, 2012). Multivariate analysis of desired attributes of contraceptive products has found differences between people of color and White people, including greater interest in products that the user can stop using at any time, are only used with intercourse, and will not affect menstrual periods among people of color (Jackson et al., 2016). Black and Hispanic women were also more likely to report that STI protection, control over whether and when to use the method, and rapid return to fertility were important. Among currently available methods, these features match closely to less-effective methods. These product attributes, especially those allowing greater control over use, as well as those related to side effects and return to fertility, may result from concerns about reproductive coercion and mistreatment and/or neglect from the health care system.

As people of color have multiple reasons for contraceptive nonuse, dissatisfaction, and discontinuation, developing a range of new products that offer a variety of product attributes would better serve this population.

People who identify as LGBTQ* or gender expansive: Non-heterosexual- identifying women, who are estimated to represent 5.6% of adult women in the United States (J. M. Jones, 2021) have rates of unintended pregnancy that are higher than those among heterosexual-identifying cis-women, especially among younger women (less than 25 years of age) (Charlton et al., 2020; Reynolds et al., 2021; Stoffel et al., 2017).

Estimates published in June 2022 based on data from the CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System indicate that more than 1.6 million adults and youth identify as transgender or gender non-conforming, or 0.6% of the population aged 13 years and older (Brown, 2022; J. M. Jones, 2021). Youth are much more likely to identify as non- cisgender: 1.4% of youth aged 13-17 years (Herman et al., 2022). While it is commonly believed that gender-affirming testosterone use is sufficient as a contraceptive, multiple studies have reported pregnancies in people who were using (or recently used) testosterone (Light et al., 2018; Moseson et al., 2021). As testosterone use during pregnancy is contraindicated because of risks to the developing fetus, individuals who are at risk of becoming pregnant and using testosterone should be advised to use highly effective birth control (World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), 2012).

Among participants in the PRIDE Study, a national, online, longitudinal cohort study of sexual and gender minority people, 186 (11%) wanted a future pregnancy, and 275 (16%) were unsure; 182 (11%) felt at risk for an unintended pregnancy (Moseson et al., 2021). People who identify as LGBTQ* or gender expansive may not be using, or not consistently using, contraception for many of the same reasons as their heterosexual- and cisgender-identifying peers. However, their contraceptive decision-making may also reflect the challenges that they have faced or expect to face in seeking health care, especially reproductive health care, and whether or not they are counseled on contraception (Stoffel et al., 2017). For transgender individuals, it may also include concerns about how side effects will affect their gender expression and identity, and the lack of information about the contraceptive effects of testosterone and the interactions between testosterone and contraception (Agénor et al., 2020; Bonnington et al., 2020; Krempasky et al., 2020). Products that would better meet the needs of these populations include those that require less interaction with the health system and a greater diversity of hormonal and non-hormonal options that would enable users to find a method that helps them affirm their gender identity without interactions with testosterone.

Those with limited resources and/or concerns about cost: Even though the Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandates that private insurers cover FDA- approved contraceptive methods with no out-of-pocket costs, there were still estimated to be more than 20.6 million women in the United States in need of publicly funded contraceptive services in 2016 (Frost et al., 2019). As such, the cost of contraceptive methods remains a barrier to use.

A review of the 2015 – 2019 NSFG data found that, if cost were not an issue, 23% of low-income female contraceptive users would use a different method, and 39% of low-income nonusers would use a method (Kavanaugh et al., 2022). Another study, using the 2015-2017 NSFG and looking at women at risk of unintended pregnancy, found that 22% of them would have preferred using a different contraceptive method if cost were not a factor (K. L. Burke et al., 2020).

Insurance status and income level: Insurance status and income level may also affect contraceptive use, but there are discrepancies in the findings related to this topic. For instance, among women at risk of unintended pregnancy, two multivariate analyses of NSFG data found that insurance status, but not income, was significantly associated with contraceptive non- use (Kavanaugh et al., 2022; J. Wu et al., 2008). A third analysis found insurance status to be significant, but did not report on income level (Mosher et al., 2015). Two others found neither to be significant after adjustments (Frederiksen & Ahrens, 2020; Grady et al., 2015). A sixth, which looked at the likelihood of using a preferred contraceptive method among women at risk of unintended pregnancy, found that it increased along with income level, but did not vary by insurance status (K. L. Burke et al., 2020). Uninsured women were also found to have higher odds of using a less-effective method than their insured counterparts (Marshall et al., 2016). While programmatic interventions and industry reforms may more quickly address cost concerns, modifications to existing methods to reduce cost, and a wider array of lower- priced generic and biosimilar brands could also help to meet the contraceptive preferences of uninsured and low-income people in the United States

People who have geographic access barriers: Having access to a wide range of contraceptive methods requires living within geographic proximity to a health care facility that offers contraception. According to Power to Decide, more than 19 million women of reproductive age in the United States are in need of publicly funded contraception and live in “contraceptive deserts” (counties without an adequate number of health centers that offer the full range of reversible contraceptive methods) and 1,149,920 United States women in need live in counties without access to a single health center that provides the full range of methods (Contraceptive Deserts 2024 | Power to Decide, 2024).

Another analysis, looking at data from 14 states and using different definitions and analysis methods, estimated that between 17% and 53% of each analyzed state’s population lived in a contraceptive desert. This analysis also found that racial minorities were overrepresented in contraceptive deserts (Kreitzer et al., 2021). The United States clearly needs more health care facilities and providers that offer contraception, especially in rural and low-income areas. The challenge of contraceptive deserts may also be addressed, at least in part, by having a broader range of contraceptive options that can be initiated, maintained over time, and/or removed without having to see a health care provider or visit a health facility.

Young people: Young people may also be underserved. For example, an analysis of the 2015-17 NSFG found that young women (aged 15-24) were more likely to report cost barriers to preferred contraceptive use compared to older women (K. L. Burke et al., 2020). While there are not contraindications specific to age (Curtis et al., 2016), providers are often reluctant to recommend certain methods to young people. Permanent methods are also generally not available to young people and those that do undergo sterilization at a relatively early age have a higher chance of regret (Danvers & Evans, 2022). In addition, the ability to access reproductive health care confidentially is especially important to adolescents and other young people (Lehrer et al., 2007). These concerns may limit a young person’s willingness to use methods that require interaction with a health care provider (Fuentes et al., 2018; R. K. Jones et al., 2005). Analysis of global data has also shown that younger populations experience much higher contraceptive failure rates, especially for user-dependent methods like pills, condoms, and withdrawal (Bradley et al., 2019). As such, young people may prefer contraceptive options that do not require interaction with a health care provider, can be used discreetly, offer dual protection, and are less user-dependent.

People older than 40 years: People who are approaching the end of their reproductive lives are also underserved by the current contraceptive options. While overall contraceptive use increases with age (Daniels & Abma, 2020), non-use of contraception among women at risk for unintended pregnancy may increase with age (Frost et al., 2007; Godfrey et al., 2016; Pazol et al., 2015). In a multivariate analysis of the 2002 NSFG among women who were at risk of an unintended pregnancy, women older than 40 had six times the odds of contraceptive nonuse compared to younger women (J. Wu et al., 2008). Unintended pregnancy rates are consistent with those among women of other ages, with estimates that 48% of pregnancies among women aged 40- 44 are unintended (Johnson-Mallard et al., 2017). Pregnancy also becomes more dangerous with age (Van Heertum & Liu, 2017). No contraceptive method is contraindicated based on age alone, but certain conditions are more common among older people, such as hypertension and venous thrombosis (Curtis et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2018; Van Heertum & Liu, 2017). As such, older women as a group have fewer contraceptive options. Reasons for non-use among older women are not well-studied. While perceived subfecundity is likely a primary reason (which providers might be able to address through education and counseling), other potential reasons include the increasing prevalence of contraindications and other health concerns (J. Wu et al., 2008). As such, older people would likely benefit from a greater diversity of methods that are highly effective and non-estrogenic.

Other potentially underserved groups

For people in larger bodies, an analysis of the 2006-2013 NSFG found that women with a BMI more than 35 kg/m2 and at risk of an unintended pregnancy were less likely to be using contraception than their lower BMI peers (Nguyen et al., 2018). Being “overweight” or “obese” does not result in any MEC 3 or 4 contraindications, but there is some evidence that emergency contraceptive pills may be less effective for those with BMIs more than 30 kg/m2 (Curtis et al., 2016; Ramanadhan et al., 2020). While people in larger bodies represent more than half of United States women of reproductive age (Hales et al., 2018; National Center for Health Statistics., 2019), there is limited socio-behavioral research on contraceptive use among people in larger bodies, so little is known about contraceptive decision-making and satisfaction among this population (Boyce & Neiterman, 2021). As such it is difficult to determine if new contraceptive methods would help meet the contraceptive needs of this growing population group.